GivingPulse

Q4 2023 Report

A holistic look at trends in giving behavior and perspectives in the U.S.

Full year 2023 + October - December 2023

Supported By:

Executive Summary

2023 Year-long Trends

♥ We profiled the most generous givers and discovered they see themselves as volunteers who give, even though they give in every form (donating money, items and advocating) more often than their peers. The most generous people are more likely to do so out of some mix of spiritual/religious mindset, a sense of privilege, or other deeper purpose that drives them.

♥ We captured more detail about respondent worldviews in Q4 that go beyond political identity, but can reliably map people along the liberal-conservative spectrum. Looking at people’s world views and political identities, we see no correlations with their levels of generosity. High, medium and low generosity groups aren’t fundamentally different in this respect, and their attitudes about generosity tend to be separate from their political ideologies.

♥ We are getting a clearer picture of the range of ways people give money for formal and informal causes. People who give to registered charities also give to informal groups and individuals, and vice versa, indicating a broad inclination to support causes and organizations in a variety of ways.

This report provides two views on GivingPulse, our weekly US nationwide survey tracking attitudes and behaviors around generosity. First, it serves as an annual report of what we observed in data we collected over 2023. Second, it serves as a quarterly report for Q4 2023, capturing data and trends over the crucial giving season.

In addition to providing some deep dives on key segments of the population, we continue to build on our holistic analysis of who is donating time, treasure, talent or influence, and what motivates them to get and remain involved.

We note the following takeaways, both for 2023 and for Q4 2023:

Q4 Specific Trends

♥ Q4 overall sees a general uptick in most generosity behaviors, as respondents are much more likely to report being solicited to support organizations and causes. However, the people who reported being solicited more often don't appear to be converting more often, or supporting new groups and causes – these rates are stable overall at 13% and 12% respectively. Increasing end-of-year conversion rates is an important challenge for the sector to tackle going forward. We see some missed opportunities for development professionals to experiment with more targeted messages and outreach, based on some emerging attitudinal profiles.

♥ Our clustering of the sample into high, medium and low generosity profiles reveals some important shifts in Q4. End-of-year giving season sees growth in the size of medium and high generosity profiles, now containing 66% of respondents collectively, with fewer people in the low-generosity pool of respondents. As more people are more likely to be solicited during the Q4 giving season, they are more likely to be more generous.

♥ The most generous people in our sample report taking input from their family and peers when giving and being raised to help others at much higher rates than other respondents, highlighting the importance of factors like peer benchmarking, modeling prosocial behaviors, and engaging in generosity as a lifestyle in driving even greater generosity among others.

♥ Over 70% of individuals who have not recently been solicited feel that generosity and giving to nonprofits are important to them, indicating a large and relatively untapped generosity market.

♥ Access to giving is not enough to drive giving. There is a need to take an active and ongoing role in prompting individuals to give. Among respondents who have not been solicited recently, those who report that they see many reminders, solicitations, and publicity for giving to nonprofits in day-to-day life are much more likely to give (a minimum of +10%) in all categories — monetary, non-monetary, formal, and informal. Those who have not been solicited recently but do report that it is easy to give to nonprofits are more likely than their unsolicited counterparts to give in the categories of money (27% vs. 18%) and giving to registered non-profits (37% vs. 26%).

♥ About half of recurring monetary donors report preferring to make a plan for giving compared with about one-third of non-recurring donors. Asking this group directly for higher value donations may be a way to further engage already recurring donors, but doing so in advance of the actual donation – appealing to their desire to plan – has even higher potential to increase the success rate of these asks.

Part 1

Generosity-Related Behaviors

Each week, we ask 100 people across the USA what generous actions they undertook within the last 7 days, for a combined sample of 1200 people each quarter. These actions could include giving money, time (volunteering), items, or advocating for causes or groups. We also ask people to distinguish whether they gave to a formal registered charity, some informal group, or an individual and whether they contributed locally, nationally, or internationally.

Each of the major types of generosity are shown below on a 4-week rolling basis covering all of 2023.

Throughout 2023, generosity across all modes fluctuated between 50% and 65% of the sample participating in at least one of the giving modes we asked about (money, items, time, or voice). Using a 4-week rolling average results in a smoothed plot that obscures end of year giving (see Q4 inset below).

In Q4¹, we saw an increase in all forms of generosity starting towards the end of October. This increase peaked during the last week of October and again in the first week of December, coinciding with 2023’s GivingTuesday on November 28. The months of November and December 2023 appear to be a plateau for monetary giving, with over 40% of respondents consistently donating money in the last 7 days from when asked. Donating items, advocating, and volunteering activities appear to closely track with giving money over this time as well.

¹ Q4 only, now using a weekly average instead of a 4-week rolling average, showing weekly variability based on 3X upsampling.

Giving by Formality

Considering what kinds of organizations, causes, and needs people support, formal, registered organizations were the most likely to be supported over 2023. Trends based on weekly reported giving to these recipients formed parallel lines with an average of 35-45% supporting individuals and informal groups, and a consistently higher proportion supporting registered charities.

Support for all causes rises throughout November 2023 and plateaus at a higher level in the last six weeks of the year, with a peak around GivingTuesday, as was observed with self-reported rates of monetary giving and item donation.

One might speculate that people support registered charities throughout the year at a higher rate because these organizations more aggressively solicit donations, but this is not the whole story. We found that people who support only formal organizations were solicited only slightly more often (42%), compared to those supporting only informal groups (34%). However, formal givers were more than twice as likely to respond to solicitation than informal-only givers: just one in five informal-only givers responded to a recent solicitation with generosity and over half of them outright ignored it. Among monetary donors specifically, 60% of informal-only givers specified that their most recent act of generosity was given without solicitation, indicating a difference in generosity drivers between informal and formal monetary donors. Similar patterns exist within the subgroups of informal volunteers as well. We dig into how attitudes among these groups differ below.

As we noted in Q3, we see consistency in the holistic way in which people give and where they give. In the fourth quarter of 2023, the breakdown of givers who participated in different kinds of generosity is nearly identical to the previous quarter, +/- 1% in each category or combination shown. In both Q3 and Q4, 25% of people gave all three: money, items, and time. The same is also true for recipient types; the population involved with each was the same as the previous quarter to within +/- 1%.

Over the whole of 2023, we found that 60-65% of respondents reported giving both to registered and informal organizations and that people who give both informally and formally comprise the largest portion of givers (57% in Q4). In contrast, 24% of respondents gave only informally (20-24% throughout 2023) and 19% supported only formal groups (19-20% throughout 2023).

Looking at Q4 data, informal giving appears to act as a gateway to more formal engagement in different kinds of generosity. 74% of respondents who give to individuals also give to formal nonprofits, as do 78% of people who give to unstructured groups. In contrast, only 63% of formal givers give to unstructured groups and 64% give on a peer-to-peer basis.

Looking specifically at monetary donation, informal-only monetary donors participate in formal giving of items and advocacy at similar rates to formal-only monetary donors and participate in all types of informal giving more. When it comes to volunteering, however, informal volunteers favor informal giving across all gift types – money, items, and advocacy – while formal volunteers participate more heavily in formal giving than informal volunteers in the same categories. There is still much overlap in formal and informal giving among volunteers, but those who engage only in informal volunteering appear to more generally favor informal engagement, while informal-only monetary donors still engage with nonprofits in other ways.

Respondents who engage both formally and informally hold certain attitudes in common more than other groups. Most of this group reports taking input from their peers about giving (57%), giving for religious reasons (62%), being raised to help others (80%), and seeing many reminders to give (78%) around them. All of these traits are consistent with a population that gives without being solicited and who don’t discriminate between registered and unregistered groups when acting.

Giving by Locality

The breakdown of giving by locality – local, national, or international giving – among givers is relatively stable across Q4. In Q4, we adjusted our survey to require that respondents answer our question about the locality of their giving, and that led to an apparent increase in giving at all levels (local, national, and international). The proportion of each (e.g. the distance between the lines in the figure below) remained relatively constant, though scaled up. It appears as though there was slightly less emphasis on international giving near the end of the year (around 8% by the end of December, compared to its peak of 12% earlier in the quarter), and a slight corresponding increase in local giving.

Part 2

Generosity Trends at a Glance

Part 3

Key Groups of Interest

Solicited vs. Unsolicited Respondents

Both weekly and monthly solicitation rates saw a substantial hike in Q4 after a relatively stable 2023, for givers and non-givers alike. The weekly solicitation rate saw an increase of 5% compared to the overall rate in Q3, while the monthly solicitation rate saw an increase of 10%. Additionally, both the weekly and monthly solicitation rates saw slight year-over-year increases of around 5% in Q4 2023 compared with the same time in 2022. By the end of December 2023, over half of GivingPulse respondents reported being solicited within the past month.

Any form of generous response to solicitation, however, remained relatively stable at 13%, compared with 10% in Q3. Somewhat surprisingly, reports of supporting a new cause or group also saw no increase in Q4, remaining stable at around 11-12% of all respondents and about 30% of monetary givers. This indicates that donor acquisition is a potential area for future improvement in end-of-year giving.

Non-givers remain the least frequently solicited group, as shown in the figure below. Compared to Q3, “planners” appear to have been more frequently solicited this quarter than spontaneous givers – only 29% of planners reported being solicited within the past week in Q3, compared with 41% in Q4. In contrast, weekly solicitation of spontaneous givers stayed about the same. This suggests that the overall increase in year-end solicitation reached a different subset of givers than had been targeted in previous quarters. This trend is similar to Q4 2022 (solicitation of "planners" was similar to Q4 this year), but solicitation of spontaneous givers skewed slightly less frequent (-5% in weekly solicitation rate, +5% in monthly solicitation rate), reinforcing that the gap between spontaneous givers and planners is widened near the end of year period.

Solicitation is of interest as a driver of generosity, but examining the characteristics of those who have not been solicited recently may tell us about opportunities in the fundraising and generosity landscape that are perhaps underrecognized. This is particularly of interest in Q4, where solicitation rates are at a year-long high. This is one key area we hope to analyze on a more regular basis in future quarterly reports.

For GivingPulse analyses, we generally consider an individual to have been solicited if the solicitation occurred within the past week. However, for this specific analysis, unless otherwise indicated, we define “solicited” as an individual who has been solicited in the past month to increase the scope of potentially relevant behaviors. This definition encompasses both people who reported being solicited in the past week and those who were solicited between one and four weeks prior to data collection.

Unsolicited Respondents: Demographic Differences

We did not see a consistent age-related trend in solicitation rates among respondents. In Q4 2023, young people were the least solicited age group, with about half of people under 25 not having been solicited in the past month. However, 50 to 64 year olds were also solicited less than the general population, even though respondents in the age groups older and younger than them reported frequent solicitation.

Among the overall sample, respondents who exhibit pro-social views and trust in nonprofits are more likely to have been solicited in the past month than those who do not exhibit these traits. However, there are no significant differences in solicitation rates between people who feel that giving to nonprofits is full of unknowns and those who feel nonprofits are not very efficient. While there may be a relationship between trust and pro-social attitudes and solicitation, we do not have evidence to suggest those who are actively more critical of nonprofits get solicited more or less.

Within the unsolicited subset of respondents, pro-social attitudes made the biggest difference in whether or not an individual gave – those who reported feeling positively about nonprofits and giving in general were about twice as likely to have given in any form than those who did not report these attitudes (57% compared with 29% of those who do not feel positively). Other attitudes that are related to increased generosity are trust in nonprofits and feelings of guilt for one’s own good fortune. Within the unsolicited group, 74% still say they enjoy giving to nonprofits and 71% say they feel everyone has a responsibility to give and help those in need, indicating a large and relatively untapped generosity market.

Unsolicited Respondents: Solicitation and Pro-Social Attitudes

While recent solicitation factors heavily into recent giving behavior, ongoing engagement is another driver of generosity. Among respondents who have not been solicited recently, those who report that they see many reminders, solicitations, and publicity for giving to nonprofits in day-to-day life give significantly more in all categories — monetary, non-monetary, formal, and informal. This suggests that, even in the absence of direct solicitation, consistent reminders and prompts to give drive giving, and perhaps those within this group would be open to more frequent or higher value gifts should they be solicited directly.

Unsolicited Respondents: Ongoing Engagement

Examining responses to solicitation among under-solicited subgroups may help expose opportunities for increased engagement, in general as well as during seasonal giving periods.

Certain combinations of factors appear to have a large impact on how people respond to solicitation. People under 25 and lower income respondents (under $25,000 per year household income) are the least likely groups to have been solicited in Q4. Likewise, these groups overall generally respond less frequently to solicitation with generosity than their counterparts (people under 25 respond similarly to people over 25 generally speaking, but when we disaggregate by distinct age groups, those under 25 are 10% less likely to respond with generosity than those between 25 and 50). Still, within age, there are some household characteristics that are worth highlighting. We looked at those who report living with children. Of this group, young people and those from lower income households are still under-solicited on a weekly basis compared to the rest of the population (26% and 25% respectively, versus 32% overall). However, those in the lowest income group with children respond similarly to the sample overall (about 40% of the time) while young people with children respond more frequently with generosity than other subgroups (60%). Similarly, lower income respondents between the ages of 25 and 35 are one of the least solicited subgroups (19% solicited within the past week), but about half of this group responded with generosity when asked. The subgroups noted represent generous people who are likely to respond positively to solicitation, but are who are not being engaged.

Another dimension to consider on this topic is respondents’ perceived ease of making a donation to a nonprofit. Those who have not been solicited recently, but who do report that it is easy to give to nonprofits, give more only in the categories of money (27% vs. 18%) and giving to registered non-profits (37% vs. 26%). This is a curious relationship as ease of giving appears to be related to only a certain type of gift while ongoing reminders elicit generosity in all forms. However, it does help to enforce the idea that access to giving is not necessarily enough to drive giving on its own.

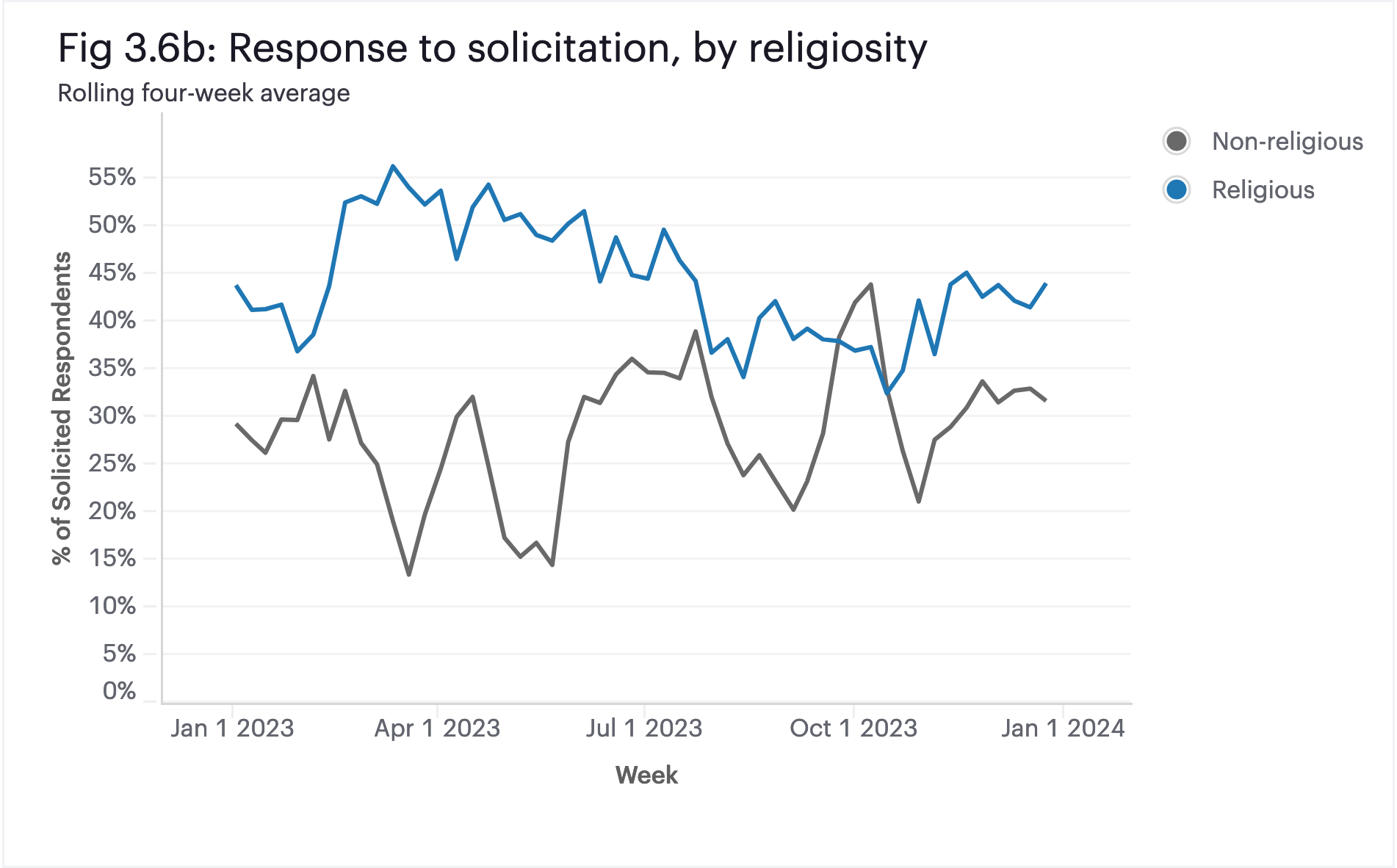

Response Rates

Non-religious people are generally under solicited and respond to solicitation less frequently than religious folks. In Q4, the non-religious subgroup saw a substantial increase in monthly solicitation, rising from 40% pre-Q4 to 50% in Q4. The solicitation rate among religious respondents comparatively rose from 48% to 54%. Response rate among non-religious folks remained stable (31%) while the response rate among highly-religious individuals (one of the most responsive subgroups) dropped from 62% pre-Q4 to 49%, one of the largest drops in response rate among any demographic subgroup. As it relates to year-end giving, it appears as though non-religious individuals are consistent in their behaviors while the conversion rate of religious folks may fall with increased year-end solicitation (although still remaining above the baseline response rate of non-religious respondents).

When those who have not been solicited recently do partake in generosity, they participate less than those who have been solicited in monetary giving (47% vs. 67%), volunteering (36% vs. 43%), and formal giving (65% vs. 76%), but give similarly in terms of informal giving (specifically peer-to-peer) and item donation. This mirrors differences in approaches to giving observed among informal givers more generally, with informal monetary donors more frequently giving without solicitation and informal-only givers preferring spontaneous, unplanned giving overall.

Nonprofits must take an active and ongoing role in prompting individuals to give in order to increase their engagement, particularly for those more focused on non-monetary and informal modes of giving.

Recurring Donors

Recurring donors represent a relatively small proportion of the GivingPulse dataset overall (typically less than 15% of all respondents in any given week). Recurring donors were relatively stable over the first half of the year, fluctuating at around 35% of monetary donors. However, there was a steep drop off in recurring donors throughout June and July, down to only 25% of monetary donors, before recovering in August back up to around 35% and fluctuating near 30% throughout Q4. It does not appear as though any events in Q4 had a significant impact on recurring donors and the recurring donor rate among monetary donors in Q4 2023 is approximately the same as the rate in Q4 2022.

Who are Recurring Donors in Q4?

Recurring donors are more likely to be full-time employed, have a high level of disposable income, and be more religious than other monetary donors. Interestingly, recurring donors tend to skew slightly younger than their non-recurring counterparts – 40% of recurring donors are under the age of 35, compared with 30% of non-recurring donors. In contrast, around 45% of non-recurring donors are above the age of 50, compared with just 31% of recurring donors.

Recurring donors are nearly twice as likely to report giving due to peer pressure than non-recurring monetary donors: in Q4, 45% of recurring donors report feelings of peer pressure or giving to fit in with others, compared with 23% of non-recurring donors. They are also more likely to report giving due to guilt for their own good fortune (55%, compared with 36% of non-recurring donors) and taking input from friends and family before giving (66%, compared with 47% of non-recurring donors). These motivations paint a picture of a donor who is keenly aware of their peers’ giving behaviors as well as the perceptions these peers may have of them.

Motivations for Recurring Giving

From the current GivingPulse questionnaire, we can only identify recurring donors who give monetarily. However, these recurring monetary donors were more likely to participate in all forms of non-monetary giving in Q4l: 65% volunteered within the past week, 63% advocated, and 78% gave items. They show a preference for giving to both formal (93%, versus 76% of non-recurring donors) and informal groups (78%, versus 59% of non-recurring donors), although they give to individuals at a similar rate as non-recurring donors. Looking specifically at monetary donations, recurring donors show a strong preference for giving to registered non-profit organizations over any other type of recipient, although they do also give to informal groups more frequently than non-recurring donors.

Other Giving Behaviors

Unsurprisingly, recurring monetary donors report giving a significantly higher amount of money in the past year compared with other monetary donors – over $5,000 on average, compared with around $2,000. In addition to their past generosity, recurring donors are also more likely to want to give more in the future compared with non-monetary donors. Nearly half of recurring donors (45%) report intentions of giving somewhat or much higher in the next year (in terms of monetary value), while this number drops to 26% for non-recurring monetary donors.

Asking directly for higher value donations may be a way to further engage already recurring donors, but doing so in advance of the actual donation – appealing to their desire to plan – has even higher potential to increase the success rate of these asks.

In terms of solicitation, recurring and non-recurring monetary donors are solicited on a weekly basis at similar rates (47% and 44% respectively), but recurring donors are much more likely to give in response to solicitation in Q4 (66% versus 55%). They also favor planning generosity over giving spontaneously – 50% reported that their most recent act of generosity was planned in advance, compared with 34% of non-recurring donors.

Despite their ongoing engagement and high volume of generosity, recurring donors appear to be highly motivated to engage even more in the generosity landscape. Given their self-reported relationships with their peers, it may be helpful to identify or target recurring givers in group settings or within existing institutions such as places of worship, schools, workplaces (about a third of recurring donors also participate in workplace giving in some form), or informal groups like sports teams or interest-based organizations.

Overall, workplace giving is a driver of increased engagement (workplace givers support more causes overall than non-workplace givers), but the magnitude of its influence is lower in Q4 compared to other times of year, perhaps due to an increased influence of other year-end factors like solicitation (generally speaking, not necessarily at work) and holiday giving.

Workplace giving is stable overall this quarter – with around 13% of respondents participating in some form – but does appear to have recovered from a downwards weekly trend starting near the end of Q2 (the graph below). Participation in workplace giving in Q4 2023 was also similar to the same period last year, at around 12% in Q4 2022.

Support for environmental and animal welfare causes (“Earth” in Table 5), which hit an unusual high at 43% of Q3 workplace givers, dropped 17% this quarter. Crises and social causes also saw a reduction in support while other causes were relatively unchanged. Generally speaking, workplace givers supported fewer causes this quarter compared with Q3 (2.6 compared with 2.9 in Q3). This trend is the opposite of what occurred among givers in general, where the average number of causes increased slightly in Q4.

Workplace Giving

The top three methods of donating money were consistent in Q4 compared with Q3: giving cash directly to a person in need (44%), in a store (27%), and online directly to a nonprofit (26%). Giving directly to a person in need remains the most common method and also increased the most in Q4 compared with Q3 (32% in Q3 compared to 44% in Q4). “In store” donations also increased slightly, up to 27% in Q4 from 21% in Q3.

See Part 7 for notes on changes to the way we asked about donation methods in Q4.

Donation Methods

Part 4

Combining Behaviors with Beliefs and Attitudes: Generosity Profiles

In the previous Q3 2023 report, we introduced a clustering framework to capture different generosity profiles, based on responses to giving behaviors captured in the survey. We describe these clusters in terms of low, medium, and high generosity and continue to see largely stable relationships within these clusters, with a few noteworthy exceptions in Q4.

Overall, there is a shift in the composition of the profiles, with more respondents identifying in the medium and high generosity profiles. The medium generosity profile, previously comprising about a third of respondents, was the largest group in Q4 and increased in size to contain close to half of respondents. Similarly, the high generosity profile increased in size from 14% to 21% of respondents. The low generosity profile shrank in proportion, from 52% in Q3 to 32% in Q4. While the low-medium-high gradient of giving behaviors holds, we now observe (in Q4) that almost no respondents in the low generosity profile engaged in giving in any form.

Two factors could be contributing to the observed shifts in the makeup of the generosity profiles from Q3 to Q4. One could be that new questions were added to the Q4 questionnaire to provide new insights into respondents’ behaviors and attitudes used in the clustering (for full details see Part 7). The second explanation is that the end-of-year giving season mobilizes some of the low-generosity pool of respondents, moving them into the medium or high generosity profiles. Of these two factors, we see stronger evidence that the second (seasonality) accounts for more of these changes than the refined questionnaire. In fact, we saw a similar shift towards larger numbers of medium and high generosity givers in our profiling model even when we excluded the new questions from it.

Characteristics of High, Medium, and Low Generosity Profiles

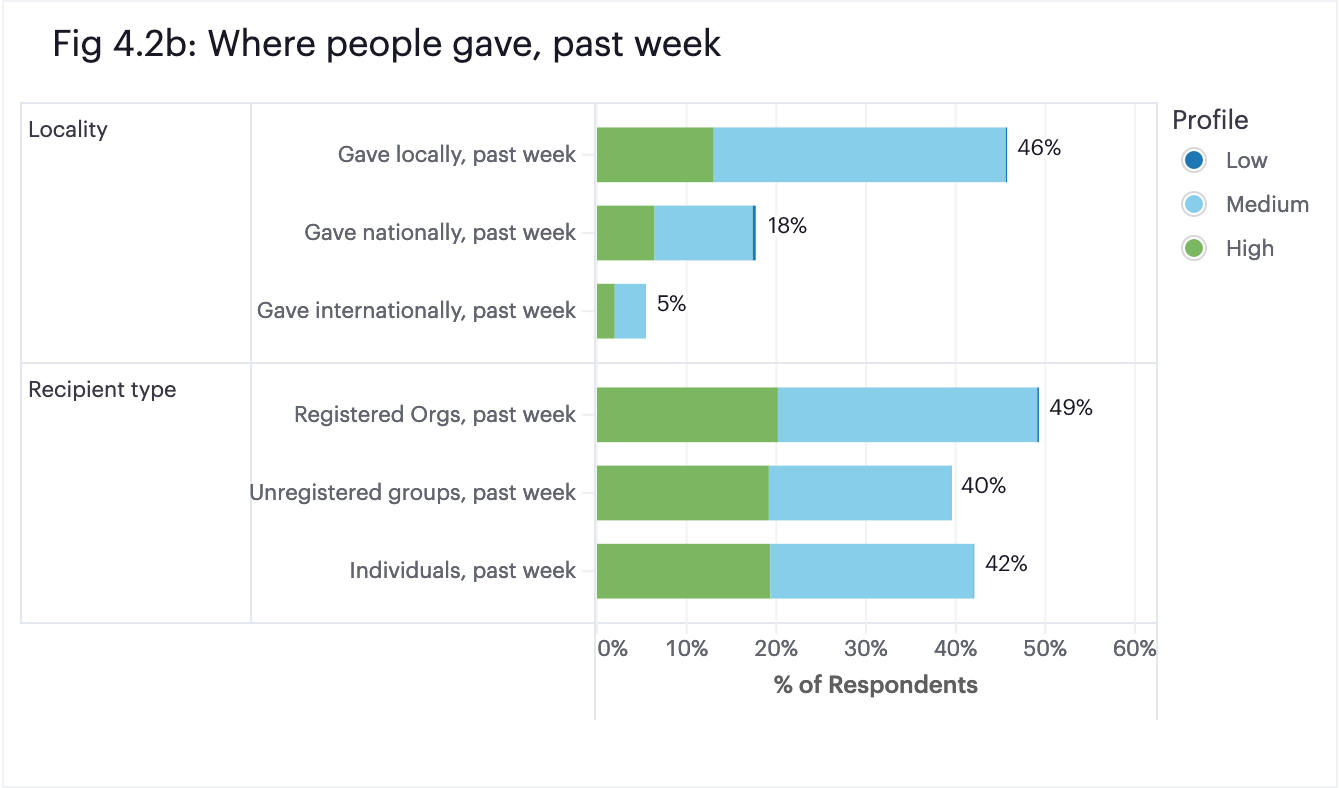

It is important to note here that respondents within the high generosity profile do not participate less in formal, monetary, or item-based giving; rather, they participate frequently and abundantly in formal, monetary, and item-based giving in addition to partaking in volunteering, advocacy, and the informal giving landscape. This means that the high generosity group contains individuals who participate actively in the generosity landscape with a wide diversity of gifts types and recipients.

Relative to the high generosity profile, the medium generosity profile is more oriented towards monetary and item donations. In terms of recipient type, giving to registered organizations is most common within the medium generosity group. Giving to unregistered groups and individuals are split relatively evenly between the medium and high generosity groups.

Giving locally is the most popular form of giving overall and is particularly popular among members of the medium generosity profile, 69% of whom give locally. National and international giving are more popular in the high generosity profile, with 30% and 9% giving in each category, respectively, compared with 23% and 7% in each category within the medium generosity profile. When respondents in the low generosity profile give, they favor giving on a national scale by a slight margin.

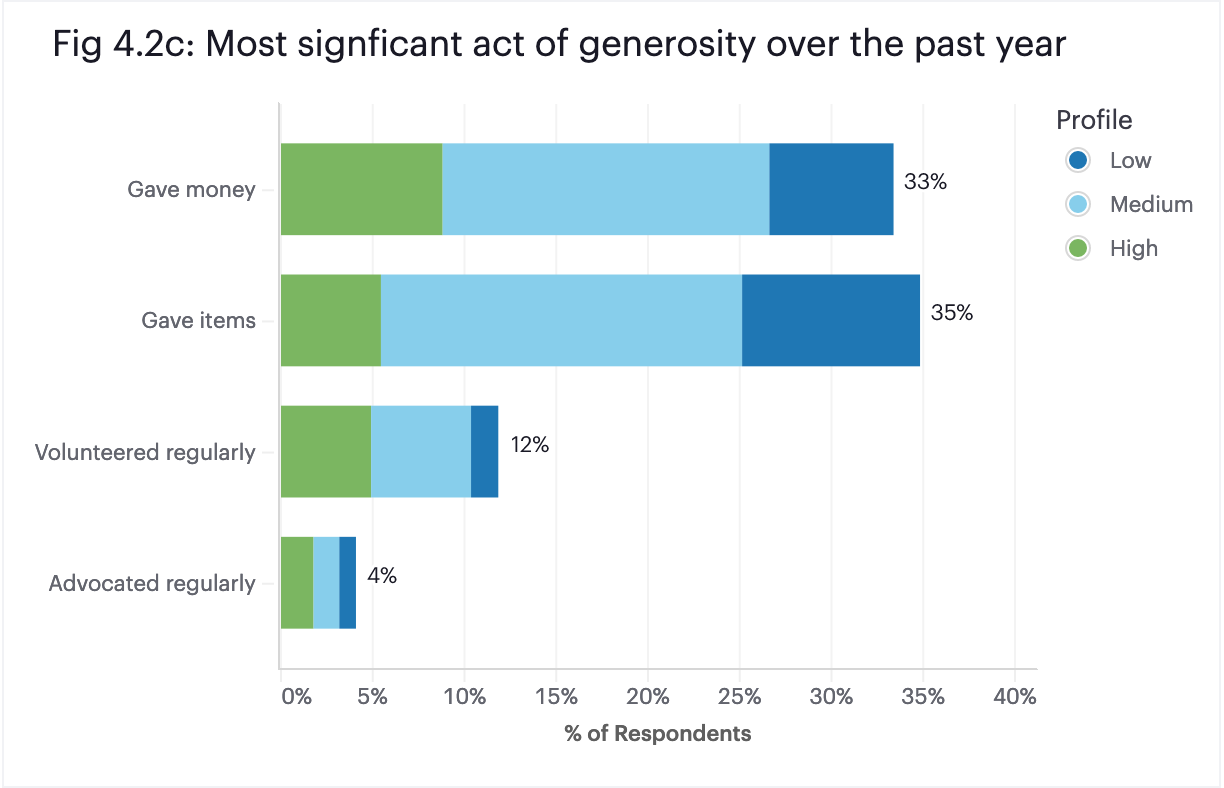

To sharpen distinctions between our giving profiles,we asked non-giver respondents when was the most recent time they gave in each category (to separate out never-givers from infrequent givers), and we asked all respondents to choose their most significant form of generosity over the past year. Responses to the latter helped to emphasize the differences between the medium and high generosity profiles in terms of non-monetary giving. Within the high generosity profile, 42% of respondents reported that giving money was their greatest contribution, while others were evenly split between giving items and volunteering regularly (23% to 25% each).

In contrast, within the medium generosity profile, the largest subset (42%) of people chose giving items as their greatest contribution, followed closely by giving money (38%), while only 12% of respondents chose volunteering regularly. Giving money as the most significant form is about equally popular between the two profiles, but more of the medium generous givers emphasize donating items while more of the high generosity subset see themselves as volunteers.

Previous research³ ⁴, suggests that volunteerism is a gateway behavior that increases all other forms of giving, and here we see that the most generous profile emphasizes being directly involved in the causes they support. Interestingly, no group placed particular emphasis on advocacy, even though 80% of the high generosity profile had recently advocated for a registered charity, compared to only 20% of the medium generosity profile. So although highly generous givers frequently advocate, volunteering is what they would identify as their most significant contribution.

All of this helps to paint a more identity-based view of an individual’s giving patterns: high generosity profile givers are primarily volunteers who give, not givers who volunteer. While they are more likely to have donated items in the past week, donated more valuable items, and advocated more for nonprofits and causes than other profiles, they are much less likely to define themselves as “item givers” than those in other generosity profiles. By comparison, the medium generosity givers see themselves more as "item givers" than "money givers", volunteers, or advocates.

The least generous profile includes folks who give infrequently or are completely uninvolved, and thus have no meaningful mode of giving. In support of this, 40% of this profile did not identify any form of giving as significant to them, compared to 5% and 2% of the medium and high profiles, respectively.

³ “Giving has a significantly smaller influence on volunteering than volunteering has on giving.” Dietz, N., & Grimm Jr., R. T. (2023). Social Connectedness and Generosity: A Look at How Social Connectedness Influences Volunteering and Giving. Do Good Institute, University of Maryland

⁴ GivingTuesday’s 2022 Lookback report

Demographic and Identity Differences between Giving Profiles

The demographic split across giving profiles was similar to Q3: income and religiosity increase as generosity increases across the profiles and the high generosity profile is on average ten years younger than the other two. People in the highly generous profile are also more likely to be non-white.

A new question added in Q4 identifies respondents who have children living at home. Across the generosity profiles, the representation of people with children living at home increases with generosity and the proportion of people with children living at home in the most generous is nearly double that of the least generous. This is likely, in part, due to the relationship between having children and age, where older folks in the lower generosity profiles are more likely to have older children no longer living at home.

This does point to an interesting relationship between family structure and generosity. Respondents with children at home are more likely to have been solicited in the past month (58%, compared with 51% of respondents without children at home) and are also more likely to respond generously to solicitation: about half gave in response to a recent solicitation, while only 34% of respondents without children responded generously. Having children (particularly young children) opens many additional gateways to solicitation, such as through school, extra-curricular activities, and youth-oriented community engagements, and the makeup of the giving profiles is likely a reflection of these factors. The question remains as to whether or not these factors have a direct influence over response rates or if other more significant factors are at play.

Starting in Q4, we asked respondents to select four of a potential twelve identity traits that best describe themselves, to go beyond their demographic features. Some identities correlate positively with generosity as described by the generosity profiles: spiritual/religious, purpose driven, and privileged all increase in prominence from the low generosity to high generosity profiles. This further adds nuance to the high generosity profile definition: these are "volunteers who give" and are more likely to do so out of some mix of spiritual/religious mindset, a sense of privilege, or other deeper purpose that drives them. In contrast, medium generous individuals were more likely to identify as ethical and honest and/or compassionate.

Six of these traits showed no variance among profiles: being more thankful, patriotic, or family first did not correlate with higher or lower generosity. Stronger cultural or ethnic affiliations, independence, or more trusting also did not correlate with higher or lower generosity.

Another change in Q4 was the addition of an eight-part political worldview question. This question was added with the goal of gaining a more nuanced view of respondents’ ideologies that go beyond liberal-conservative or Democrat-Independent-Republican spectrums. These worldview questions can be examined on their own or used to map individuals to the Pew Political Typology as a proxy for their placement on a left-center-right political spectrum. This approach is based on extensive work by the Pew Research Center and was initially tested by GivingTuesday in our Growing Generosity in Florida report, released in fall 2023.

Overall, unlike some of their attitudinal differences, the generosity profiles are more similar in terms of their worldviews. The low generosity group is most likely to select “not sure” in response to all statements and is most divided for nearly all options compared to the other profiles, highlighting their less engaged and less cohesive behavioral profile. There are fewer ideological differences between the medium and high generosity profiles, with one of the most noticeable differences being agreement with the statement “A decline in the share of Americans belonging to organized religion is bad for society” (36% in the medium profile vs. 47% in the high profile). The majority of respondents did not agree with that statement overall, but agreement is more popular among more religious respondents, who are highly represented in the high generosity profile.

Mapping each respondent to a Pew type (see Methodology), we observe that all three generosity profiles contain members representative of the full political spectrum. Respondents in the low generosity profile are slightly concentrated on the center-right of the spectrum, while the medium generosity profile is split between the left and the “Populist Right” typology. The high generosity profile has the highest representation of “Democratic Mainstays” and the lowest representation of the “Populist Right”, but is overall relatively evenly distributed across the spectrum. While there may be differences in how generosity manifests, it is important to note that individuals of all political persuasions and worldviews are present across the low, medium, and high generosity profiles.

Differences in Attitudes about Giving and Nonprofits: Percent who Agree with Each Statement

The attitudes of the different generosity profiles are similar to Q3, with pro-social attitudes, feelings of guilt, and feelings of peer pressure to give being most prominent in the high generosity profile. Compared with Q4 2023, sentiments did not change much within the low and medium generosity profiles (+/- 6% for any given question) and comparisons across profiles remained the same, but there were some larger shifts within the high generosity profile. Notably, reports of giving due to peer pressure and guilt decreased by 18% and 12% year-over-year, respectively. These figures have been trending slightly downwards in the overall sample since Q4 2022 and this decrease is most pronounced within the smallest group who reports this attitude profile most heavily.

According to a newly added question, the high generosity profile reports taking input from their family and peers at a much higher rate (69%) than either the medium or low generosity profiles. Rates of reporting that one was raised to help others and give to nonprofit organizations also increase between the low to high generosity profiles. These factors in combination suggest that GivingPulse’s most generous givers are highly influenced by those around them, both in terms of their upbringing and their ongoing relationships with family and peers. This highlights the significance of community in fostering generosity and emphasizes the importance of factors like peer benchmarking, modeling prosocial behaviors, and engaging in generosity as a lifestyle in driving even greater generosity among others.

Attitudes about Nonprofits: Percent who Agree with Each Statement

We updated the wording of one attitudes statement from “There are many reminders, solicitations, and publicity for giving to nonprofits in day-to day life” to “I see many reminders, solicitations, and publicity for giving to nonprofits in day-to day life”. This resulted in an overall drop in agreement from 80% in Q3 to 68% in Q4.

One of the largest shifts observed in Q4 2023 was in self-reported financial strain. Although the overall agreement with the statement “Donating money to charities provides too much of a financial strain on me” remained stable compared with Q3, this rate increased by about 10% within the medium generosity profile, now accounting for up to nearly half of medium generosity respondents. This is still the lowest rate of financial strain among any of the profiles; however, the gap is much smaller than in previous quarters (a minimum of 19% between the rate in the medium profile and the next highest rate in another profile between Q1 and Q3) and in Q4 2023. This shows that financial strain, while still a factor in generosity, defined peoples’ behaviors less in Q4 than at other times of year. The question remains as to whether this is an ongoing trend or a more seasonal effect.

Political Worldview and Generosity

Examining Q4 generosity by way of an eight-part worldview question and corresponding Pew political typologies reveals some interesting patterns (or lack thereof) in high-level giving behaviors across the political spectrum.

There are no discernible trends in giving to registered non-profits across the worldview spectrum. While some subgroups do tend to be less engaged in formal giving (the “Outsider Left”, in particular), it does not appear as though giving to registered nonprofits is associated with either the nature or extremity of one’s political views. Where we do observe a trend, however, is in the categories of peer-to-peer giving and informal giving, broadly speaking. Respondents in the center are far more likely to engage in informal giving than respondents at either political extreme. Among “Stressed Sideliners”, who typically display low interest in politics, 83% of givers engaged in informal giving in Q4. This proportion decreases consistently outwards towards the right and left ends of the spectrum where 69% of “Faith and Flag Conservatives” and 67% of “Progressive Left” individuals gave informally.

As we discussed in relation to the generosity profiles, generosity exists in abundance regardless of political affiliation, and it appears as though this extends to engagement with nonprofits as well. At the same time, it appears as though those who are less politically engaged, or less strongly politically affiliated, are more active in the form of informal or peer-to-peer giving.

Part 5

How the World and Crises Affect Giving

Crisis and Awareness

The top crisis of concern amongst GivingPulse respondents in Q4 was the Israel-Hamas War, beginning October 7, 2023. In the month of October, about 23% of all respondents reported awareness of a crisis involving one or several of the words “Israel”, “Hamas”, “Gaza”, or “Palestine”. This drops to about 10% of all respondents for the full quarter with lower awareness in November and December, due to declining interest in the Israel-Gaza war.

Other notable crises include ongoing awareness of the Maui, Hawaii wildfire (the top crisis in Q3), various earthquakes worldwide (mainly Afghanistan), and tornadoes in Tennessee.

On a yearly scale, the top crises of 2023 were the earthquake in Turkey and Syria in February, tornadoes in Mississippi in March, wildfires in Maui in August, the Israel-Hamas war starting in October, and multiple flooding events throughout the year (California, Libya, Vermont, and Florida, to name a few).

While crisis response was at a year-long low of 18% in Q3, it bounced back up to 30% overall for Q4. It is possible that an increase in overall generosity as well as the increase in solicitation in Q4 played a role in crisis response (70% of those who responded to crisis reported having been solicited within the past month, compared with 55% of those who had not yet responded or already ignored). It is also possible that the nature of the crises in Q4 – humanitarian need as a result of conflict, mainly – spurred an increase in responses compared with Q3. However, given the comparable levels of response in Q1 (25%) and Q2 (32%) in the absence of such disasters, this is unlikely to be the case.

Methodology note: Prior to Q4, GivingPulse’s crisis response question had five options and respondents had the option to choose multiple responses. Starting in Q4, the options “Not yet, unsure if will” and “Shared with others” were dropped and respondents were only allowed to select one response. The increase in responses to “Already responded” and “Ignored it” are likely due in part to these updated response options.

Respondents falling in the “Not yet, but intend to” category tend to be overall more generous in all categories than those who have ignored an identified crisis, but they are overall less generous than those who have already responded. Compared to those who responded with generosity, they exhibit a similar level of pro-social attitudes and trust in nonprofits, but are less likely to report giving due to peer pressure (29% vs. 49%) or guilt (40% vs. 56%).

Interestingly, financial strain does not appear to factor into crisis response, at least between those who have already responded and those who intend to respond. Respondents who report that they intend to give are solicited at a similar rate to others, but most commonly select “not yet” in response to solicitation too (43%), and the givers amongst them are much more likely to report having given unsolicited than those who already responded to a crisis (67% vs. 49%). Overall, this subgroup of respondents is generous, but appears to be less receptive to prompts to give or the urgency of a crisis. This behavioral profile opens up an interesting area for future research into the nature of response to different crises as well as tactics that will convert intentions to actions.

Part 6

About The Sample

The GivingPulse sample is weighted to be representative of the age, gender, and regional distribution (Northeast, Midwest, West, and South) of the US according to the results of the most recent census. The overall sample composition is thus consistent week-to-week and quarter-to-quarter with respect to these demographic traits.

Regional variation:

Givers were 13% less prevalent in the midwest this quarter compared to last, and major donors (people who gave $2,500 or more last year) in this region dropped 30%. In contrast, large donors increased by 40% in western states (24% of respondents in Q3, compared with 33% in Q4).

Employment:

32% of non-givers are full-time employed, compared to 46% of givers. Similarly, 20% of non-givers are unemployed, compared to 13% of givers.

Demographics:

In Q4, we began asking about religiosity on a three-level scale (Not at all/Somewhat/Very) instead of the five-level scale that was used pre-Q4 (Not at all/A little/Somewhat/Quite/Very). Comparing Q4 results with a binned version of the Q3 results, we see the shifts in the table below, with the Q4 sample skewing slightly less religious than in Q3.

The number of high income individuals (making greater than $100,000 per year) dropped 10%, from 23% of respondents in Q3 to 20% of respondents in Q4. Among givers, this decrease was less apparent (only -6%), while the number of lower income (making less than $50,000 per year) givers rose 10% from 36% to 39%).

The proportion of self-identifying African American respondents increased 20% overall this quarter (12% to 15%). This increase was more pronounced among non-givers (+33%, from 10% to 14%).

Part 7

Changes to the Survey in Q4 of 2023

We changed our questionnaire between Q3 and Q4 of 2023 to clarify our intent on certain questions and remove others that had not yielded any meaningful results over the past year, or that had little to no influence on the clustering analysis. Periodically culling poor-performing questions enables us to test more effective alternatives. Some of the more major changes include:

We removed the category “blood and organ donation” from our giving taxonomy questions, reducing the number of options in the “Gave in other ways” category.

We revised a question that asked directly about political affiliation (Republican/Democrat/Other) and to a more nuanced version that asks about worldviews, so that we can understand this facet of a person in many countries, regardless of party affiliation.

We added a question asking respondents to select a set of words that they identify most strongly with as a way of gaining a better understanding of drivers of giving and respondents’ identities beyond their demographic traits.

We split one context question with eight answers into three separate questions about solicitation, planning, and locality of their most recent generous act. The previous question allowed respondents to choose any combination of options, while the new format only allows one selection for each question.

We asked about four additional attitudes regarding giving that mattered in other surveys.

We replaced a question about marital status (Married/Divorced/Single/Widowed, Common-law-partnership) with a simpler one that appears to relate more closely to generosity behavior: do you have kids living with you at home or not?

We recategorized the donation methods we ask about to be clearer and to work everywhere in the world. This affected Figure 7.1, as explained below.

Changes in how we ask about donation methods likely account for the large variance observed in Q4 of 2023, compared to earlier quarters. In the first three quarters of 2023 these behaviors only shifted by +/- 6 percentage points, but we see +/- 16 percentage points after changes in how we define the methods. Some transactions were inherently ambiguous in the previous draft (e.g. using a nonprofit's website on a phone in a browser to donate money via Venmo), but we believe the revised categories now capture the most important distinctions between these types of interactions.

The largest shift observed was a 16% drop in the selection of "Other." This is likely due to us mapping four additional options that were available in Q3 to one option in Q4.

Some of the observed shifts are surprising: "Gave cash directly to a person in need" was one of 13 options previously, and now only one of nine. The wording on the question did not change, but we underlined part of the answer option in the latest version: "Gave cash directly to a person in need". We saw a 12 percentage point increase (from 32% of respondents choosing this option to 44%). It is possible that the reduced number of options as well as underlining the question contributed to this, in addition to actual shifts in Q4 behaviors⁵.

⁵ Significant shifts from minor changes in content appearance have been noted by others before, such as using a lighter/darker font: https://www.globalgiving.org/learn/ggtestlab/how-cognitive-psychology-and-font-colors-can-drive-donations/

Here are some additional more minor changes to the survey in Q4 2024:

Stopped asking about other special giving days beyond GivingTuesday. We used these to compare with GivingTuesday but the incidence of people knowing about any of the five other days was quite low.

Removed two options from questions about a person's response to events, to limit it to three clear options (did something, did nothing, plan to do something):

You have not responded, and may or may not do so

You passed it on to someone else / You shared it with others to raise awareness

Clarified that merely "liking" something on facebook is not considered advocacy, though sharing messages over social media counts.

Stopped tracking "donating blood or body parts" as a form of generosity, because of low frequency.

Stopped asking about political donations. There was no pattern here that related to other generosity behaviors, though we intend to bring this back in Q2-2024 for the 2024 political season just in case things change.

Added Veterans/Military to the other NTEE cause areas we track.

Added Middle Eastern/North African as a tracked ethnicity, and removed Christian, Muslim, Jewish from that question.

Reduced employment statuses from 6 to 4: Fully employed, part-time employed, unemployed, and retired.